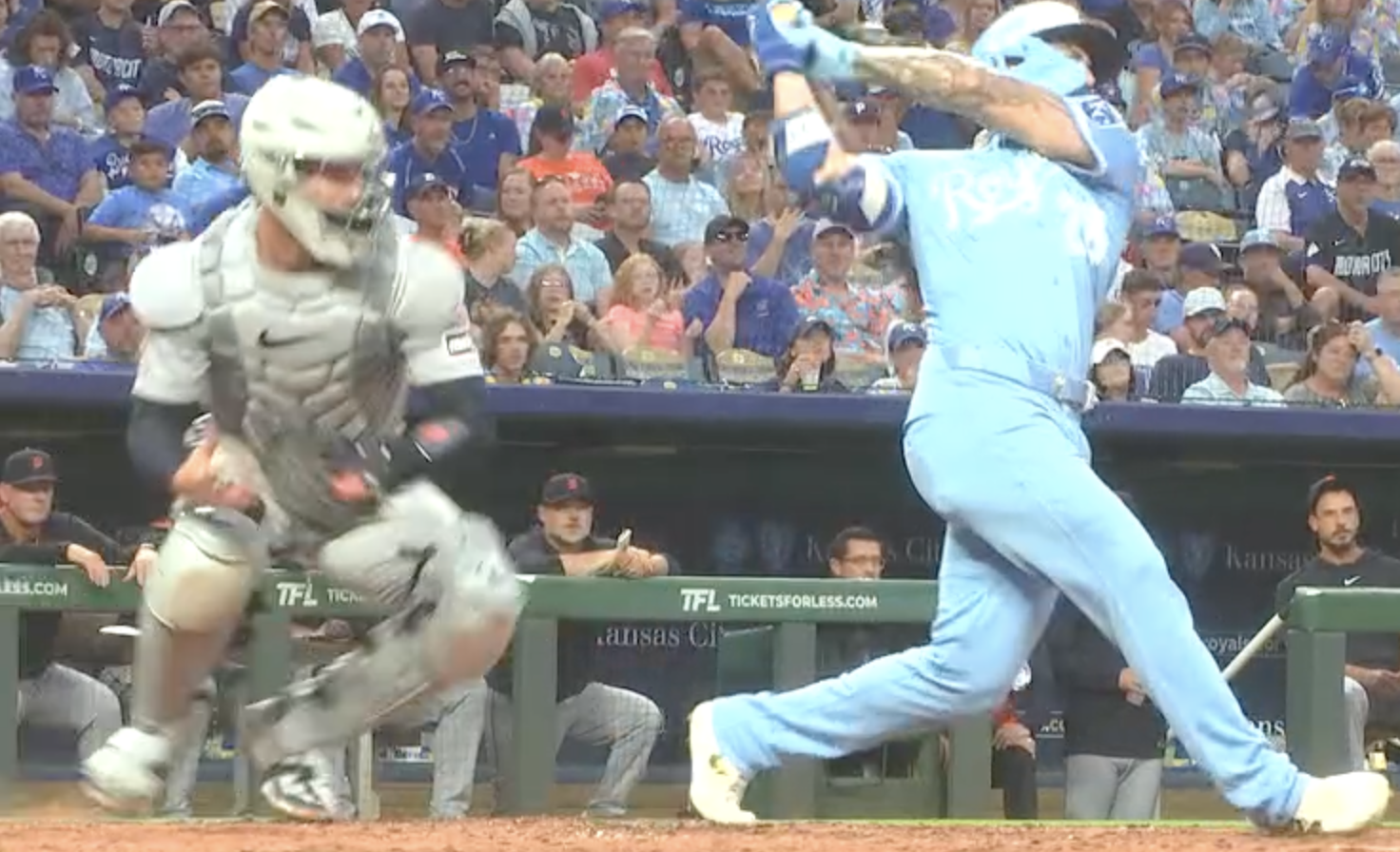

In the clip above, you can see Kyle Higashioka shift his body to his glove side to receive the pitch and, as he stands up and gets turned towards 2B, he brings his foot directly underneath his center of gravity.

Again, no wasted energy or time.

THROWING FROM THE KNEES:

To conclude this section, let's address a burning question in many minds: "But what about throwing from your knees?"

We've seen countless instructional videos promoting the throw from the knees to 2B as not just flashier but more effective than standing up. Moreover, we have witnessed other "well-respected" catching instructors irresponsibly teaching this approach, disregarding scientific research and testing on the biomechanics of athletic throwing patterns. In short, athletes who have not established these patterns should never throw from their knees under any circumstances.

We have advocated for the standing approach as a far more efficient method of throwing to 2B for as long as I can remember. However, let's take a moment to outline all the reasons why relying on this approach, even with an advanced and efficient athletic throwing pattern, is not advisable for consistent results or as the default approach to throws.

REASON #1: It is NOT safe for the majority of athletes.

Using a throw from the knees as the default approach to throwing is dangerous for most catchers. The reason is simple. There is a significant amount of misleading information available regarding throwing technique and mechanics. Unfortunately, some of this misinformation comes from those at the top of the instructional hierarchy, resulting in high-level athletes exhibiting throwing pattern deficiencies. Until athletes have established efficient throwing patterns that do not put their arms at risk, they should NEVER attempt a throw from their knees. Doing so will put even greater stress on their arm since the bulk of the excess stress in the throw will be felt there. In essence, if you cannot throw efficiently while standing up, it is unrealistic to expect that you can do it from your knees. If I encountered a player with exceptional movement patterns from a prone position but flawed standing up, I would still work tirelessly to fix the problem while throwing from a standing position.

REASON #2: It is NOT faster.

When we consider the throw, we often focus on technique and overlook the fact that it is essentially a mathematical problem: getting "Object A" to "Object B" before "Object C" reaches "Object B." Our goal is to achieve this in the most efficient way possible. Throwing from our knees is not the answer. We cannot generate the same velocity from our knees as we can from a standing position. If we can, it indicates a suboptimal throwing motion in general rather than the ability to throw from our knees. In other words, if the velocity of a throw from the knees is the same as the velocity while standing up, there is something fundamentally wrong with the throwing technique.

To gain insights from experts in the field, I reached out to the team at Driveline in Seattle, WA. Led by Kyle Boddy, they have revolutionized the game with a scientific approach and quantifiable metrics for analyzing athletic movement patterns. Their understanding of the human body and throwing skill is unmatched worldwide. Here's what former catcher Maxx Garrett from Driveline had to say about our question:

"I think it is pretty safe to say that you can put more force into the ground from the standing position. From the standing position, I would think that you will be able to create more Ground Reaction Force and greater hip rotation, which will lead to greater velocities. Ball flight takes up a great portion of pop time, so creating this velocity is an important thing to think about."

It is generally assumed that ground reaction force is greater when throwing from a standing position than when throwing from the knees. Although Maxx mentioned they hadn't conducted specific testing on this, it aligns with the principles of physics and biomechanics. Ground reaction force refers to the force exerted by the ground on a body in contact with it. In simple terms, you can create more ground reaction force while standing compared to kneeling, resulting in higher velocities. This is not a matter of opinion; it is a fact.

Some may argue, "But coach, I release the ball significantly faster, so the lower velocity doesn't matter." Here's the issue: we must not overlook the math behind the throw. For every 5 mph decrease in velocity from throwing from the knees, we need to reduce at least 0.10 seconds in our release time. The problem is that most catchers are not actually quicker when releasing from their knees; often, it's exactly the same. The overwhelming majority of catchers cannot release the ball a tenth of a second faster from their knees. Additionally, most catchers will lose 10-20 percent of their throwing velocity when throwing from their knees. If a catcher can only throw 60 mph from a standing position, they will likely throw anywhere from 48-54 mph from their knees—a range that guarantees a slower overall throw from the knees. Despite all these reasons, some coaches continue to hold steadfast to the notion. Even if we were to concede that it might be faster (which it's not—let's not forget that), we still have to confront the fact that...

REASON #3: …It's far less consistently accurate.

In general, the throw from the knees is less accurate. Much of it has to do with the stability of our body while executing the throw, such as shin guards sliding on the ground instead of having the traction provided by cleats when standing. The spikes on our footwear give us better control of our bodies. I cannot count the number of times I have witnessed catchers unleashing a throw from their knees only to see it fail to reach the bag, sail high, or veer off-line to the right or left. We have significantly more control over the direction of our throw while standing. Therefore, it is unwise to take that risk when we are not gaining any real advantage from it and, at the very least, potentially putting ourselves in harm's way.

The only explanation I've heard that I could even partially understand or respect is that it "LOOKS COOLER and is MORE INTIMIDATING." However, the only reason this holds true is because coaches at higher levels keep instructing catchers to do it, especially in softball. But you know what isn't intimidating? A runner safely reaching second base due to a late throw by the catcher or, worse, a runner advancing to 3B or Home because our inaccurate throw evades the infielder. The reputation and control of the running game at the highest levels allow certain catchers to do whatever they want, but that does not apply to everyone. One frequently mentioned name is Benito Santiago. While he was captivating to watch behind the plate, his throwing ability was barely average. His release time was consistently over seven-tenths of a second, and his pop time exceeded 2.00 seconds—both below the MLB average. In terms of success throwing out runners, he was only 4% better than the average MLB catcher throughout his career. To put that in perspective, Ivan "Pudge" Rodriguez was 15% better than his competition throughout his career. Santiago led the league in caught stealing percentage only once in his 20-year MLB career. We are not talking about an elite throwing catcher; we are discussing someone who made it look good when it worked.

Now, it's possible that in certain circumstances, an athlete's subpar athleticism and physical constraints may lead them to develop a high-level throwing motion that is more efficient from their knees. However, in over 22 years of working with over 16,000 students, I have never encountered a catcher for whom that was true. With all this said, it is not to suggest that throwing from the knees should not be a skill in a catcher's repertoire. There are situations where a throw from the knees should be the default approach. Here are some examples:

1. Throwing off a block when the catcher has previously established highly efficient throwing patterns.

2. A pickoff to 1B or 3B when the catcher has previously established highly efficient throwing patterns.

3. A straight steal of 3B, with the pitch bringing the catcher to their knees when the catcher has previously established highly efficient throwing patterns.

4. If, while tracking down a pop-up, the catcher trips, falls, catches the ball, and the runner on 1B inexplicably starts chatting with friends in the stands while standing 5 feet off the bag... and the catcher has previously established highly efficient throwing patterns!

Some argue that catchers who throw out runners from their knees will impress coaches at the next level and deter the opposing team from running. However, throwing from the knees does not accomplish either of those things. What matters is the runner safely reaching second base.

Throwing from the knees may be effective in certain situations (as outlined above), but as a default approach, it is not faster or more effective. It also has the potential to damage an athlete's arm if they have not first established an efficient throwing motion. Therefore, it should not be taught until those athletic movement patterns have been developed.

THROWS TO 3B:

When it comes to making a throw to 3B on an attempted steal, it's essential for catchers to understand the rulebook. Most importantly, a right-handed hitter does not need to move out of the way of a catcher's throw. They are entitled to the batter's box, and as long as they don't impede the throw intentionally or unintentionally, they can stand still in the catcher's way. It's the catcher's responsibility to create a throwing lane to 3B.